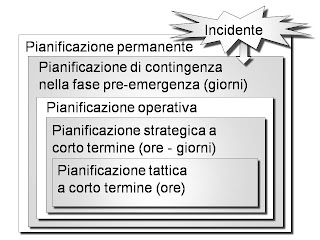

Fig 1. Forms of planning for relief operations.

Figure 2. A training course in civil defense.

The management of rescue operations following disasters, crises and emergencies is a relatively new field, but, nevertheless, may draw on a tradition of study and research which dates originally from the year 1920 (Prince 1920, Barrows 1923) and that is strong and supported from 1950 onwards. While the field is sometimes included in the science programs of management, in reality it is a discipline in itself, fondata su diverse basi. I suoi obiettivi fondamentali sono quattro (Waugh e Tierney 2007):

- in situazioni di crisi, abbinare le risorse a disposizione con il fabbisogno urgente;

- permettere diversi enti ed organizzazioni di lavorare insieme in modo efficace sotto condizioni difficili e probabilmente insolite;

- comunicare con unità operative e centri operativi in modo tale da mantenere il livello di comando e controllo delle situazioni di crisi;

- applicare i provvedimenti del piano di emergenza, insieme a rilevanti protocolli operativi e patti di assistenza mutua, secondo le esigenze del disastro.

Questi processi richiedono una conoscenza di come lavorano le diverse organizzazioni and various specialists in the rescue. Therefore, the management of emergencies (emergency management ) is a cross-discipline (Phillips 2005), which must develop a language and a culture shared by at least 35 professions and disciplines involved in one way or another, in the 'disaster cycle' (mitigation, preparedness, response, recovery and reconstruction). The complex process of coordinating emergency work requires the ability to understand and work with representatives of various disciplines, in fact, to "speak their language in order to understand their views and help them cope with the emergency effectively (Alexander 2002).

La gestione delle emergenze è una disciplina olistica, concreta e dedicata alla soluzione di problemi pratici (McEntire 2003). Essa è fortemente legata alla pianificazione d'emergenza, alla gestione della continuità degli affari aziendali (business continuity management, BCM; Elliott et alii 2001), alla risposta medica all'emergenza ed ad altri campi di natura altamente pratica. Gli imperativi sono di salvare le vite umane, aiutare a coordinare il soccorso delle vittime, contenere e ridurre i danni, e assicurare un rapido ritorno ad accettabili condizioni normali.

Nel mondo moderno, ci sono numerose associazioni alle quali i coordinatori di emergenza possono aderire. L'Istituto di Protezione Civile e Gestione delle Emergenze (ICPEM, already Institute of Civil Defense and Disaster Studio) was founded in the United Kingdom in 1937 and is a company filled with academic titles, the oldest in the world. The UK Emergency Planning Society (EPS) has 3000 members, while the International Society of Emergency Coordinators (IAEM) has 4500. The latter offers a professional qualification of global validity, the examination for Certified Emergency Manager (CEM). Throughout the world, IAEM vigorously promotes eight principles of emergency management (see Table 1). From these it is clear that emergency management requires skills such as leadership, the ability to coordinate, plus a strong knowledge of emergency (Haddow and Bullock 2003).

Worldwide, there are at least 400 books on the market (in English) relevant to emergency management. Since 1950 in this field and related subjects at least 19,000 books and scholarly articles have been published, also in English and worldwide. When teaching emergency management, it is important to use the fruits of research (Coppola 2008) and combine theory with experience derived from managing the events of the past (Alexander 2000). Both of these aspects are essential. The theory provides a kind of "road map" of the chaotic emergency situations (Drabek 2006). Using the theoretical concepts as a guide, the people trained in this field should understand highly complex processes. Included in the list command and control, evacuation, vulnerability analysis (social, economic and physical), communication (again with physical and social components), notice, search and rescue, and medical and health response to emergencies.

An emergency coordinator must be able to create, disseminate, maintain, enforce and update contingency plans for three types (Fig. 1). First there is the permanent plan that has the resources in a crisis. This requires the formulation (with great precision) of scenarios depicting the impact and dynamic response, the study of the available resources and procedures to be applied. Secondly, there contingency planning will be the pre-impact and then, thirdly, the short-term strategic planning to make during the emergency phase. The plans of all types must be compatible with different levels of government, different areas and jurisdictions, and emergency services. There is also an international dimension that includes the European Union and the Organization of the United Nations, for example in respect of the International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UN-ISDR) and the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). The work of coordination of emergency response can be local, inter-regional (in the case of national emergency) or European (in the case of an event affects more than one country or that it be so great as to require the input of resources from abroad). It may be of interest to developing countries, as in the case of humanitarian missions. In any case, for planning and managing these contingencies standardized methods exist and should be taught (ISDR 2005).

In terms of threats and scenarios, the modern emergency coordinator must understand and respond to a wide range of risks and events. Natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes are a category. Technological risks such as collisions and transport toxic rain is another. A third is made up of social risks such as rallies and mass protests, and the fourth category is the risk of intentional acts, terrorism, which also includes the collection of intelligence and military intervention and civil defense. In addition there are emerging risks (Schieb 2006). Of these pandemics are generally considered the most pressing, followed by the effects of climate change and the disruption of basic services, or impairment of the food chain. Based on these risks, the landscape of civil protection could change radically in just a few months, so flexibility is a vital quality to teach the coordinator of emergency operations (see table 1).

the coordination of emergency is a revolution taking place di tecnologia di comunicazione ed informazione. Questa ha avuto effetti profondi sulla risposta a disastri e crisi (Marincioni 2007). Quindi, è importante insegnare sia gli aspetti tecnici che il lato umano della comunicazione, compresa l'apposita ricerca in sociologia, psicologia e percezione. Dato che circa l'80% della pianificazione di emergenza costituisca un problema geografico e territoriale, i sistemi di informazione georeferenziata (GIS) sono un arnese essenziale (Dubois et alii 2006). Questi servizi ed attività saranno probabilmente concentrati nel centro operativo e il coordinatore di emergenza deve acquisire una piena conoscenza del suo potenziale e delle sue funzioni.

Recentemente è successa un'enorme crescita nella gestione continuity of business enterprise (BCM - see above). This new framework has been applied to both the public and the private economy. Its main objective is to make companies and governments resistant to disasters and crises, and enable it to overcome the hardships without going bankrupt, which is a very strong risk for companies not prepared. For the public sector in times of disaster is to prevent substantial disruptions to their services. In promoting preparations, the emergency coordinator plays a key role (Halliwell 2008).

In summary, the emergency coordinator must help to create resilience. This term comes from the rheology, the science materials, and is rapidly becoming a distinct philosophy of the organization against threats, risks, crises and disasters (Batabyal 1998). In creating resilience, the challenge is to ensure the professionalization of emergency coordinators through the rigorous application of training and the creation of recognized and respected. It 'also important to ensure that the work of emergency management in the hands of well trained professionals, in other words there is an institutional role for graduates in this field. Great progress is made in some countries, notably the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Sweden and India (Berkes 2007). It 'important that Italy will not be left back.

If education is the engine of the professionalization of the role of coordinator of emergency, which is the best way to organize it? Despite the attractions of the basic degree course in civil defense, a clear consensus that the best solution is that of higher degree. A basic degree in another field (sociology, architecture, engineering, geology, psychology or any discipline pertaining to the work of disaster reduction) can serve as a preparation on which to lay deep and solid work experience and training in civil protection transverse (ie, interdisciplinary), offered as a degree of specialization (Fig. 2). In the latter, the student, studies already mature, learning to coordinate, manage, and interviews with various specialists in order to create the 'common culture' in the civil protection has strong need (Neal 2000). The product of a process like this should be someone with flexibility and adaptability, two qualities are essential in emergency situations and risk.

Citations

Alexander, DE 2000. Scenario methodology for teaching Principles of Emergency Management. Disaster Prevention and Management 9 (2): 89-97.

Alexander, DE 2002. Principles of Emergency Planning and Management . Terra Publishing, Harpenden, UK; Oxford University Press, New York, 340 pp.

Barrows, H.H. 1923. Geography as human ecology. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 13: 1-14.

Batabyal, A.A. 1998. The concept of resilience: retrospect and prospect. Environment and Development Economics 3(2): 235-239.

Berkes, F. 2007. Understanding uncertainty and reducing vulnerability: lessons from resilience thinking. Natural Hazards 41(2): 283-295.

Coppola , D.P. 2008. The importance of international disaster management studies in the field of emergency management. In Emergency Management in Higher Education: Current Practices and Conversations . Public Entity Research Institute, Fairfax, Virginia (Capitolo 5).

Drabek, T.E. 2006. Social Dimensions of Disaster: a teaching resource for university faculty. Journal of Emergency Management 4(5): 39-46.

Dubois, G., E.J. Pebesma e P. Bossew 2006. Automatic mapping in emergency: a geostatistical perspective. International Journal of Emergency Management 4(3): 455-467.

Elliott, D., E. Swartz e B. Herbane (curatori) 2001. Business Continuity Management: A Crisis Management Approach . Routledge, Londra, 206 pp.

Haddow, G.D. e J.A. Bullock. 2003. Introduction to Emergency Management . Butterworth-Heinemann, Londra, 272 pp.

Halliwell, P. 2008. How to distinguish between 'business as usual' and 'significant business disruptions' and plan accordingly. Journal of Business Continuity and Emergency Planning 2(2): 118-127.

ISDR Secretariat 2005. Know Risk . Tudor Rose, Londra, 376 pp.

Marincioni, F. 2007. Information technologies and the sharing of disaster knowledge: the critical role of professional culture. Disasters 31(4): 459-476.

McEntire, D.A. 2003. Searching for a holistic paradigm and policy guide: a proposal for the future of emergency management. International Journal of Emergency Management 1(3): 298-308.

Neal, D.M. 2000. Developing degree programs in disaster management: some reflections and observations. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters 18(3): 417-438.

Phillips, B.D. 2005. Disaster as a discipline. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters 23(1): 111-140.

Prince, S. 1920. Catastrophe and Social Change: Based Upon a Sociological Study of the Halifax Disaster . Studies in History, Economics and Public Law no. 94. Colombia University Press, New York, 151 pp.

Schieb, P-A. 2006. Emerging risks and risk management policies in selected OECD countries. In W.J. Ammann, S. Dannenmann e L. Vulliet (curatori) Risk 21: Coping with Risks Due to Natural Hazards in the 21st Century . A.A. Balkema, Taylor & Francis, Londra: 31-40.

Waugh, W.L. Jr e K. Tierney 2007. Emergency Management: Principles and Practice for Local Government (2a edizione). ICMA Press, International City Management Association, Washington, D.C., 366 pp.

_______________________________________________

Tabella n. 1. I principi IAEM della gestione dell'emergenza

1. Comprensiva : per quanto riguarda i disastri, i coordinatori di emergenza dovrebbero prendere in considerazione tutti i rischi, tutte le fasi, tutti gli impatti e tutti gli interessati.

2. Progressive: emergency coordinators should anticipate future disasters and take preventive and preparatory measures to create disaster-resistant and resilient communities.

3. Risk Management: to coordinate the priorities and resources, emergency coordinators should use the principles of good risk management, based on the identification of hazards and an analysis of risks and impacts.

4. Integrated: emergency coordinators should ensure a degree of unity among all levels of government and all elements of the community.

5. Collaborative : coordinators emergenza dovrebbero creare e mantenere rapporti larghi e sinceri tra persone ed organizzazioni atti ad incoraggiare fiducia, promuovere un'atmosfera da squadra, creare consenso e facilitare comunicazione.

6. Coordinata : per arrivare ad obiettivi comuni, i coordinatori di emergenza dovrebbero sincronizzare le attività di tutti gli interessati.

7. Flessibile : quando si tratta di affrontare la sfida dei disastri, i coordinatori di emergenza dovrebbero utilizzare approcci creativi e innovativi.

8. Professionale : i coordinatori di emergenza dovrebbero utilizzare un approccio basato su principi scientifici, radicati nella conoscenza accademica della materia, con ampio riferimento alla formazione, l'addestramento, l'etica, il servizio pubblico e il costante miglioramento.

NB: Questo principi costituiscono la base della definizione del profilo professionale del coordinatore di emergenza, come utilizzato nell'esame del CEM – Certified Emergency Manager .

_________________________________________________

The management of rescue operations following disasters, crises and emergencies is a relatively new field, but, nevertheless, may draw on a tradition of study and research which dates originally from the year 1920 (Prince 1920, Barrows 1923) and that is strong and supported from 1950 onwards. While the field is sometimes included in the science programs of management, in reality it is a discipline in itself, fondata su diverse basi. I suoi obiettivi fondamentali sono quattro (Waugh e Tierney 2007):

- in situazioni di crisi, abbinare le risorse a disposizione con il fabbisogno urgente;

- permettere diversi enti ed organizzazioni di lavorare insieme in modo efficace sotto condizioni difficili e probabilmente insolite;

- comunicare con unità operative e centri operativi in modo tale da mantenere il livello di comando e controllo delle situazioni di crisi;

- applicare i provvedimenti del piano di emergenza, insieme a rilevanti protocolli operativi e patti di assistenza mutua, secondo le esigenze del disastro.

Questi processi richiedono una conoscenza di come lavorano le diverse organizzazioni and various specialists in the rescue. Therefore, the management of emergencies (emergency management ) is a cross-discipline (Phillips 2005), which must develop a language and a culture shared by at least 35 professions and disciplines involved in one way or another, in the 'disaster cycle' (mitigation, preparedness, response, recovery and reconstruction). The complex process of coordinating emergency work requires the ability to understand and work with representatives of various disciplines, in fact, to "speak their language in order to understand their views and help them cope with the emergency effectively (Alexander 2002).

La gestione delle emergenze è una disciplina olistica, concreta e dedicata alla soluzione di problemi pratici (McEntire 2003). Essa è fortemente legata alla pianificazione d'emergenza, alla gestione della continuità degli affari aziendali (business continuity management, BCM; Elliott et alii 2001), alla risposta medica all'emergenza ed ad altri campi di natura altamente pratica. Gli imperativi sono di salvare le vite umane, aiutare a coordinare il soccorso delle vittime, contenere e ridurre i danni, e assicurare un rapido ritorno ad accettabili condizioni normali.

Nel mondo moderno, ci sono numerose associazioni alle quali i coordinatori di emergenza possono aderire. L'Istituto di Protezione Civile e Gestione delle Emergenze (ICPEM, already Institute of Civil Defense and Disaster Studio) was founded in the United Kingdom in 1937 and is a company filled with academic titles, the oldest in the world. The UK Emergency Planning Society (EPS) has 3000 members, while the International Society of Emergency Coordinators (IAEM) has 4500. The latter offers a professional qualification of global validity, the examination for Certified Emergency Manager (CEM). Throughout the world, IAEM vigorously promotes eight principles of emergency management (see Table 1). From these it is clear that emergency management requires skills such as leadership, the ability to coordinate, plus a strong knowledge of emergency (Haddow and Bullock 2003).

Worldwide, there are at least 400 books on the market (in English) relevant to emergency management. Since 1950 in this field and related subjects at least 19,000 books and scholarly articles have been published, also in English and worldwide. When teaching emergency management, it is important to use the fruits of research (Coppola 2008) and combine theory with experience derived from managing the events of the past (Alexander 2000). Both of these aspects are essential. The theory provides a kind of "road map" of the chaotic emergency situations (Drabek 2006). Using the theoretical concepts as a guide, the people trained in this field should understand highly complex processes. Included in the list command and control, evacuation, vulnerability analysis (social, economic and physical), communication (again with physical and social components), notice, search and rescue, and medical and health response to emergencies.

An emergency coordinator must be able to create, disseminate, maintain, enforce and update contingency plans for three types (Fig. 1). First there is the permanent plan that has the resources in a crisis. This requires the formulation (with great precision) of scenarios depicting the impact and dynamic response, the study of the available resources and procedures to be applied. Secondly, there contingency planning will be the pre-impact and then, thirdly, the short-term strategic planning to make during the emergency phase. The plans of all types must be compatible with different levels of government, different areas and jurisdictions, and emergency services. There is also an international dimension that includes the European Union and the Organization of the United Nations, for example in respect of the International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UN-ISDR) and the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). The work of coordination of emergency response can be local, inter-regional (in the case of national emergency) or European (in the case of an event affects more than one country or that it be so great as to require the input of resources from abroad). It may be of interest to developing countries, as in the case of humanitarian missions. In any case, for planning and managing these contingencies standardized methods exist and should be taught (ISDR 2005).

In terms of threats and scenarios, the modern emergency coordinator must understand and respond to a wide range of risks and events. Natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes are a category. Technological risks such as collisions and transport toxic rain is another. A third is made up of social risks such as rallies and mass protests, and the fourth category is the risk of intentional acts, terrorism, which also includes the collection of intelligence and military intervention and civil defense. In addition there are emerging risks (Schieb 2006). Of these pandemics are generally considered the most pressing, followed by the effects of climate change and the disruption of basic services, or impairment of the food chain. Based on these risks, the landscape of civil protection could change radically in just a few months, so flexibility is a vital quality to teach the coordinator of emergency operations (see table 1).

the coordination of emergency is a revolution taking place di tecnologia di comunicazione ed informazione. Questa ha avuto effetti profondi sulla risposta a disastri e crisi (Marincioni 2007). Quindi, è importante insegnare sia gli aspetti tecnici che il lato umano della comunicazione, compresa l'apposita ricerca in sociologia, psicologia e percezione. Dato che circa l'80% della pianificazione di emergenza costituisca un problema geografico e territoriale, i sistemi di informazione georeferenziata (GIS) sono un arnese essenziale (Dubois et alii 2006). Questi servizi ed attività saranno probabilmente concentrati nel centro operativo e il coordinatore di emergenza deve acquisire una piena conoscenza del suo potenziale e delle sue funzioni.

Recentemente è successa un'enorme crescita nella gestione continuity of business enterprise (BCM - see above). This new framework has been applied to both the public and the private economy. Its main objective is to make companies and governments resistant to disasters and crises, and enable it to overcome the hardships without going bankrupt, which is a very strong risk for companies not prepared. For the public sector in times of disaster is to prevent substantial disruptions to their services. In promoting preparations, the emergency coordinator plays a key role (Halliwell 2008).

In summary, the emergency coordinator must help to create resilience. This term comes from the rheology, the science materials, and is rapidly becoming a distinct philosophy of the organization against threats, risks, crises and disasters (Batabyal 1998). In creating resilience, the challenge is to ensure the professionalization of emergency coordinators through the rigorous application of training and the creation of recognized and respected. It 'also important to ensure that the work of emergency management in the hands of well trained professionals, in other words there is an institutional role for graduates in this field. Great progress is made in some countries, notably the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Sweden and India (Berkes 2007). It 'important that Italy will not be left back.

If education is the engine of the professionalization of the role of coordinator of emergency, which is the best way to organize it? Despite the attractions of the basic degree course in civil defense, a clear consensus that the best solution is that of higher degree. A basic degree in another field (sociology, architecture, engineering, geology, psychology or any discipline pertaining to the work of disaster reduction) can serve as a preparation on which to lay deep and solid work experience and training in civil protection transverse (ie, interdisciplinary), offered as a degree of specialization (Fig. 2). In the latter, the student, studies already mature, learning to coordinate, manage, and interviews with various specialists in order to create the 'common culture' in the civil protection has strong need (Neal 2000). The product of a process like this should be someone with flexibility and adaptability, two qualities are essential in emergency situations and risk.

Citations

Alexander, DE 2000. Scenario methodology for teaching Principles of Emergency Management. Disaster Prevention and Management 9 (2): 89-97.

Alexander, DE 2002. Principles of Emergency Planning and Management . Terra Publishing, Harpenden, UK; Oxford University Press, New York, 340 pp.

Barrows, H.H. 1923. Geography as human ecology. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 13: 1-14.

Batabyal, A.A. 1998. The concept of resilience: retrospect and prospect. Environment and Development Economics 3(2): 235-239.

Berkes, F. 2007. Understanding uncertainty and reducing vulnerability: lessons from resilience thinking. Natural Hazards 41(2): 283-295.

Coppola , D.P. 2008. The importance of international disaster management studies in the field of emergency management. In Emergency Management in Higher Education: Current Practices and Conversations . Public Entity Research Institute, Fairfax, Virginia (Capitolo 5).

Drabek, T.E. 2006. Social Dimensions of Disaster: a teaching resource for university faculty. Journal of Emergency Management 4(5): 39-46.

Dubois, G., E.J. Pebesma e P. Bossew 2006. Automatic mapping in emergency: a geostatistical perspective. International Journal of Emergency Management 4(3): 455-467.

Elliott, D., E. Swartz e B. Herbane (curatori) 2001. Business Continuity Management: A Crisis Management Approach . Routledge, Londra, 206 pp.

Haddow, G.D. e J.A. Bullock. 2003. Introduction to Emergency Management . Butterworth-Heinemann, Londra, 272 pp.

Halliwell, P. 2008. How to distinguish between 'business as usual' and 'significant business disruptions' and plan accordingly. Journal of Business Continuity and Emergency Planning 2(2): 118-127.

ISDR Secretariat 2005. Know Risk . Tudor Rose, Londra, 376 pp.

Marincioni, F. 2007. Information technologies and the sharing of disaster knowledge: the critical role of professional culture. Disasters 31(4): 459-476.

McEntire, D.A. 2003. Searching for a holistic paradigm and policy guide: a proposal for the future of emergency management. International Journal of Emergency Management 1(3): 298-308.

Neal, D.M. 2000. Developing degree programs in disaster management: some reflections and observations. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters 18(3): 417-438.

Phillips, B.D. 2005. Disaster as a discipline. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters 23(1): 111-140.

Prince, S. 1920. Catastrophe and Social Change: Based Upon a Sociological Study of the Halifax Disaster . Studies in History, Economics and Public Law no. 94. Colombia University Press, New York, 151 pp.

Schieb, P-A. 2006. Emerging risks and risk management policies in selected OECD countries. In W.J. Ammann, S. Dannenmann e L. Vulliet (curatori) Risk 21: Coping with Risks Due to Natural Hazards in the 21st Century . A.A. Balkema, Taylor & Francis, Londra: 31-40.

Waugh, W.L. Jr e K. Tierney 2007. Emergency Management: Principles and Practice for Local Government (2a edizione). ICMA Press, International City Management Association, Washington, D.C., 366 pp.

_______________________________________________

Tabella n. 1. I principi IAEM della gestione dell'emergenza

1. Comprensiva : per quanto riguarda i disastri, i coordinatori di emergenza dovrebbero prendere in considerazione tutti i rischi, tutte le fasi, tutti gli impatti e tutti gli interessati.

2. Progressive: emergency coordinators should anticipate future disasters and take preventive and preparatory measures to create disaster-resistant and resilient communities.

3. Risk Management: to coordinate the priorities and resources, emergency coordinators should use the principles of good risk management, based on the identification of hazards and an analysis of risks and impacts.

4. Integrated: emergency coordinators should ensure a degree of unity among all levels of government and all elements of the community.

5. Collaborative : coordinators emergenza dovrebbero creare e mantenere rapporti larghi e sinceri tra persone ed organizzazioni atti ad incoraggiare fiducia, promuovere un'atmosfera da squadra, creare consenso e facilitare comunicazione.

6. Coordinata : per arrivare ad obiettivi comuni, i coordinatori di emergenza dovrebbero sincronizzare le attività di tutti gli interessati.

7. Flessibile : quando si tratta di affrontare la sfida dei disastri, i coordinatori di emergenza dovrebbero utilizzare approcci creativi e innovativi.

8. Professionale : i coordinatori di emergenza dovrebbero utilizzare un approccio basato su principi scientifici, radicati nella conoscenza accademica della materia, con ampio riferimento alla formazione, l'addestramento, l'etica, il servizio pubblico e il costante miglioramento.

NB: Questo principi costituiscono la base della definizione del profilo professionale del coordinatore di emergenza, come utilizzato nell'esame del CEM – Certified Emergency Manager .

_________________________________________________